This was published a few years ago, but I just came across it recently. It is Close Encounters With Buildings, an article by Jan Gehl, Lotte Johansen Kaefer, and Solvejg Reigstad. Gehl is one of the world’s leading urban designers and author of several books including the pathbreaking Life Between Buildings.

“Close Encounters With Buildings” provides an explanation and definition of pedestrian-scale facade design. It reviews several systems for understanding and classifying the characteristics of facades which can either enhance or diminish the attraction and liveliness of pedestrian space.

The building facades, display windows and shop interiors that are closest to walkers have the greatest sensory and emotional impacts. The authors point out that pedestrians at 1 meter (3 feet) distance from a building facade can see less than 3 meters (10 feet) of the building. At 5 meters (16 feet) distance from a building, pedestrians can see about 3.5 meters (11 feet). So the pedestrian scale experience of a building is primarily the experience of the ground floor.

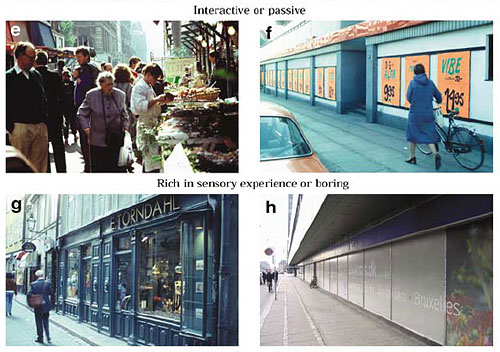

Pedestrians traverse the streetscape at walking speed, at which fine details of architecture and public space design may be perceived. But contemporary buildings are most often built at the car scale, at which functional variety and sensory experience get ratcheted down to the most limited and restricted expression possible. “Modern cities are heavily influenced by confusion over these two scales,” write the authors. As a result, the richness of the public realm is sacrificed.

Carefully differentiated treatment of the interface between building and city was taken for granted in the past: building units were small, shops modest and public space designed primarily to accommodate pedestrian traffic. Building techniques allowed rich detailing that included pillars, pilasters, nooks and niches. Functions and doorways were close together and goods for sale eye-catching. City space became almost inherently intense and inviting due to the short distance between experiences and great functional variety.

Gehl whimsically labels these as “close encounter” buildings. They are also called “active” facades and their performance can be measured both subjectively and objectively. For a study of street activity in Copenhagen, the Centre for Public Space Research at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts developed an evaluation scale to classify the pedestrian attractiveness of facades.

- CATEGORY A: Small units, many doors (15-20 doors per 100 m). Large variation in function. No blind and few passive units. Lots of character in facade relief — primarily vertical facade articulation. Good details and materials.

- CATEGORY B: Relatively small units (10-14 doors per 100 m). Some variation in function. Few blind or passive units. Facade relief. Many details.

- CATEGORY C: Mix of large and small units (6-8 doors per 100 m). Modest variation in function. Some blind and passive units. Modest facade relief. Few details.

- CATEGORY D: Large units. Almost no variation in function (2-5 doors per 100 m). Many blind or uninteresting units. No facade relief. Few or no details.

- CATEGORY E: Large units, few or no doors (0-2 doors per 100 m). No visible variation in function. Blind or passive units. Uniform facades with no relief. No details, nothing to look at.

The study used the following metrics to measure the performance of the different facade categories:

- Number of people passing by the facade per hour

- Speed at which pedestrians passed the facade

- Number of people who turned their heads towards facade as they passed by

- Number of people who stopped in front of the facade

- Number of people who went in or out of a door in the facade

- Number of people who carried out other types of activities or stayed in front of the facade; type of activity and where it took place.

The study found that active facades consistently performed better. Overall, the more active facades had seven times more activity than the less active facades.

These categories have been used to map city districts and classify the attractiveness of streets and blocks. Once the maps are completed, codes may be written for frontage standards that support existing contexts, or that upgrade to a higher level of pedestrian orientation. This has been carried out with positive results in Stockholm and other cities.

And of course, the subjective, intangible qualities of pedestrian environments are equally important. Gehl and his colleagues provide a brief review of cities in Europe and Australia that have had success in creating districts with active, pedestrian-oriented facades, and the design guidelines they employed.

Instead of focusing solely on how many people walk, stop, sit and stand, it is also important to look at quality content, wealth of experiences, and yes, the simple delight in being in cities. … The overriding planning principle has to be: first life, then space, then buildings.

Kudos to Gehl and his colleagues for recognizing the subjective and objective qualities, the tangible and intangible aspects, that are important for creating good civic space. Too often those qualities get short shrift (if not complete dismissal) in new construction. And credit also is due to the officials who have formally recognized and mandated the importance of active, “close encounter” building facades in their cities.

Resources

Close Encounters With Buildings, originally published as “Nærkontakt med huse” in the Danish architectural magazine Arkitekten, September 2004 issue. English translation by Karen Steenhard.

Close Encounters With Buildings, a version published in the Spring, 2006 issue of Urban Design International, has more legible versions of certain diagrams and photos.