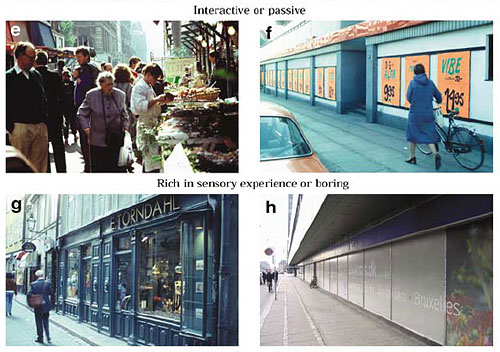

Architects and urban designers have debated streetscapes for many decades. As early as 1889, the Austrian architect Camillo Sitte wrote of the importance of continuous, connected building facades that lined streets and defined their form. Beautiful public spaces have a sense of enclosure, said Sitte; they feel like outdoor rooms. A few years later the German architect and planner Josef Stübben covered the height-to-width proportion of streets in his handbook of city planning.

In the 1920s and 30s the architect Le Corbusier issued several emphatic rejections of such ideas. “DEATH TO THE STREET,” he thundered, decrying the traditional streetscape as dangerous, unhealthy, chaotic, and congested. The ideas promulgated by Corbusier and other modernist planners were in tune with the needs of the motor industry: dispersed towers, wide buffers, and large highways. The design of new highways and arterials in cities came to resemble the auto-oriented visions of modernist planners.

The chorus of voices defending traditional streetscapes snowballed during the 1960s-1990s. Hundreds of new streetscapes were built based on traditional patterns. Infill development re-established traditional streetscapes in existing city districts. Today one can find both patterns actively promoted in all cities of the world. The debate continues as vigorously, and sometimes as contentiously, as ever.

One condition keeping the debate alive is the various arguments, theories, and polemics lack solid empirical support. Many designers and engineers have a gut feeling about the best way to design streetscapes but statistical evidence is thin. Several streetscape surveys have been developed, and researchers have used them to carry out a few studies. The surveys require teams that manually evaluate each street segment using checklists of tens or hundreds of factors. The process is laborious, slow, and expensive; and as a result, the studies to date have been limited and somewhat inconsistent.

That’s why a thesis by Chester W. Harvey titled “Measuring Streetscape Design for Livability Using Spatial Data and Methods” (2014) is an important advance in the urban design field. Harvey developed a computerized method to evaluate the essential form of streetscapes. He tested the results against a survey of streetscape appeal and found significant relationships. The theories and speculations of the past 125 years have finally been confirmed with a large sample set: streetscapes shaped like outdoor rooms are perceived to be safer and more attractive to walk in. And that is only the beginning, as the method offers many other potential avenues of investigation.