Which types of urban roadways are the most dangerous? Major arterial or minor arterial? Freeway or local street? The field of motor-vehicle safety statistics is more than a century old. One would expect such a mature field to have settled the basic question of the best way to report fatality risk. But that’s not the case, and what’s more, the most common method of reporting risk may be mathematically invalid. We may be getting an incorrect understanding of the types of roadways that have the highest fatality risk.

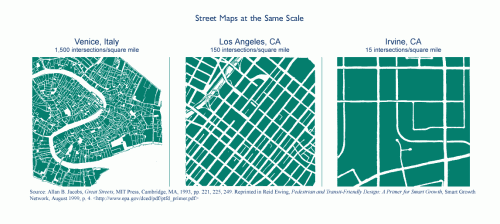

Engineers and traffic officials often say freeways are the safest roadways and local streets are the most dangerous. That fits the view of mainstream engineering, which points out that local streets have the closest spacing of driveways and intersections, and therefore the densest occurrence of “conflict points” where crashes can happen. Freeways and expressways have strictly controlled access in order to eliminate intersections and driveways.

That view of safety is one of the main justifications for the mandated federal policy called functional classification. The goal of functional classification is to channel a large percentage of traffic onto a small percentage of roadways, specifically freeways, highways, and arterial roads. Those roadway types are the most elaborate and designed to carry high volumes of fast traffic, often with full or partial access control. Functional classification has been very successful at achieving its basic goal of channeling and concentrating traffic.

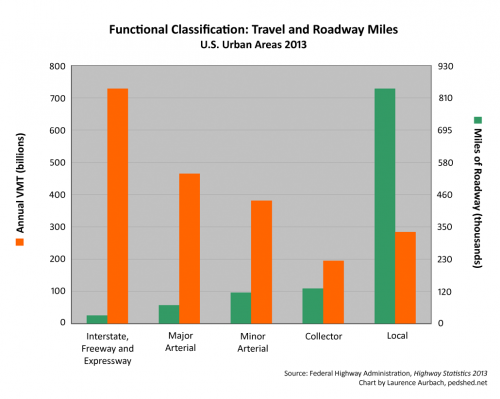

Chart 1: Distribution of urban traffic and urban roadway miles. The chart shows the United States’ skewed pattern of travel, which is largely the product of hierarchical and dendritic roadway layouts supported by functional classification.

Chart 1 shows how functional classification sorts roadways into a range of types. The nation’s skewed distribution of traffic is apparent. Seventy-seven percent of traffic is carried by eighteen percent of roadways — by the so-called “higher-class” freeways, expressways, and major arterials. Traffic in the official statistics is reported as vehicle miles traveled (VMT). National VMT is the sum of annual state estimates, which are based on gasoline consumption, traffic counters, personal travel questionnaires, and other methods.

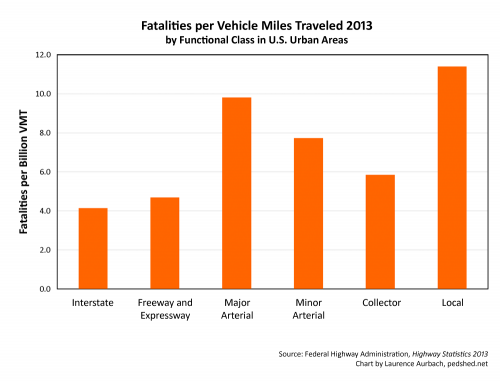

To compare the safety of roadways, engineers and administrators adjust the raw statistics to account for exposure. The Federal Highway Administration (and indeed the entire mainstream traffic engineering field) does that by dividing the number of fatalities by VMT. In other words, they use travel mileage as the measure of risk exposure. The chart based on that metric looks like this:

Chart 2 confirms the mainstream view. Interstates are the safest facilities and local streets are the most dangerous. But is that view truthful? Actually, the official statistics contain a critical logical flaw. VMT (that is, travel distance) is the product of speed and time. Therefore speed is fundamentally intertwined in the fatalities-per-VMT metric. The way the variables are related produces the following outcome. For any given amount of travel time, and assuming identical roads and drivers, the fatalities-per-VMT metric will always report that faster speed is safer (see Appendix 1).

But that’s opposite to basic physics and everything we know from traffic safety research. Faster speed is more dangerous on most roadways, and it’s certainly more dangerous on full-access urban streets and arterials. Does a better metric exist?

Every field has its foundational working concepts and the field of traffic engineering is no exception. It has a concept called functional classification, which is the core, guiding idea underlying the roadway system of the United States and many other nations. Functional classification is the conceptual foundation of the auto-dependent built environments where most Americans live.

Every field has its foundational working concepts and the field of traffic engineering is no exception. It has a concept called functional classification, which is the core, guiding idea underlying the roadway system of the United States and many other nations. Functional classification is the conceptual foundation of the auto-dependent built environments where most Americans live.