This is part 2 of a series. See also Introduction • Latter Half of the 20th Century • Neighborhood Walking • Neighborhood Crime • Vehicle Miles and Traffic • Crash Safety

Before the automobile age, people didn’t think much about connectivity. It was taken for granted that well-connected street networks were the best way to build cities. The routes between buildings had to be as convenient as possible because everyone moved slowly, compared to today’s motorized transport. Most city folk traveled at 2-4 mph (the speed of walking) and even those with vehicles didn’t move much faster than 7-9 mph (the speed of a horse and buggy).

The invention of the automobile changed all that and gushers of oil provided the fuel. Growth of vehicle production was explosive. America went from 8,000 vehicles in 1900 to 9.2 million in 1920 and 23 million in 1930. In 1916, military trucks allowed the French to win the battle of Verdun. It was the first time motorized vehicles were decisive in a large battle. World War I was pivotal in motorizing the U.S. military.

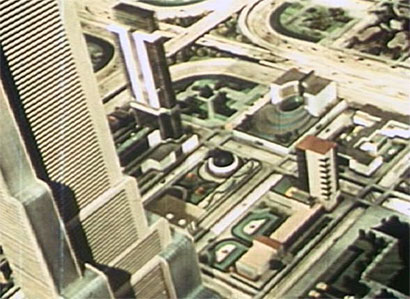

Some architects and planners believed they could transmute the power of mass motor vehicle use into a force for good: a force to alleviate poverty, squalor and oppression of the masses. European modernists like Charles-Edouard “Le Corbusier” Jeanneret and Ludwig Hilberseimer were revolutionaries, fascinated with large-scale schemes that would wipe away the old order and comprehensively reorganize cities for personal mobility via the automobile. The selling points were speed, efficiency, cleanliness and progress, a message that played especially well in America.

Ludwig Hilberseimer, Hochhausstadt, 1924

The American regionalism movement denounced overcrowded, unhealthy cities and the growing threat posed by automobile collisions. As mass ownership of cars and trucks became a reality in the 1920s, the regionalists along with their allies in government, and eventually the real estate industry, began to rethink thoroughfare patterns. Here was something new, they reasoned: door to door service at 30 mph or better! Gradually they concluded that all the old assumptions about connectivity could be tossed aside. Drawing on the Garden City tradition, their solution was a universal pattern of low density cul de sacs set in superblocks.

These initiatives were blows to connected streets in multiple ways. Disconnected street networks became the default pattern throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

Read more →